Release of the Report ‘Life, World and Agency: Children in Contact with Railways by AIWG – RCCR

Posted on January 15, 2019

12th January, 2019

LIFE WORLD AND AGENCY: Children in Contact with Railways

A Report by All India Working Group for Rights of Children in Contact with Railways

In 2009 the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR) forwarded their recommendations for ‘Safeguarding the Rights of Children at Railway Platforms’ to the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD). The Railways then constituted Child Welfare Committees (CWC) at railway stations. However, the Child Welfare Committees, as set up by Railways, were not the statutory ones prescribed under the Juvenile Justice Act, 2000.

In 2012, a Writ Petition was filed in the Delhi High Court alleging that NCPCR’s recommendations were not being implemented. When the Railway Board and NCPCR drafted a Standard Operating Procedure, Civil Society Organisations, academicians, and child rights activists protested the violation of the High Court Order. NCPCR then agreed to support a study to formulate a ‘care and protection’ policy (other than the prevalent rescue-and-restore) to meet the children’s requirements.

When NCPCR withdrew its offer, the All India Working Group for Rights of Children in Contact with Railways (AIWG-RCCR) was founded to promote the concept of agency of children. Agency is reflected in the decisions children make, and these decisions are never ‘free’ choices but constrained by the environment. AIWG-RCCR launched this research to document the options which children choose, in their given context, and the organic structures that support these options.

The study is divided into two phases. In the first phase, a schedule was administered to over 2,000 children, who had spent more than one month at the station, at 127 railway stations across India, in collaboration with 40 child rights groups and their specially oriented workers. The questionnaire was embedded into an application named ‘ChildSpeak’ designed for mobile phones and tablets to ensure objectivity, data protection, and rapid data entry and analysis.

In the second phase, detailed histories of 48 selected children, who had spent more than six months in contact with the railways, were collected around issues emerging from the first phase, by a set of ten Core and Academic Researchers who were carefully selected to provide a comfortable environment for the children to speak while fully respecting their privacy. A four-day orientation workshop was held at Nagpur with these Researchers.

The picture of ‘agency’ that emerges from the survey data is that half the children are coming to the railway station to earn money, another quarter wishes to live on their own terms, and three-fourth retain regular contact with their families. Only one-tenth did not wish to stay in touch with their families at all. The railway station provided opportunities to collect bottles, beg, and sell all kinds of goods for survival; it also gave space to sleep and play, and make friends.

Over half of the children experienced harassment at the station, mostly by the police, and some by other children. Over two-thirds of those being harassed moved to safer locations at the station, while another half searched for environments suited to their terms. More than two-thirds had friends at the station to call upon for sustenance and one-third depended upon NGOs. About a quarter, though, were apprehensive that NGOs would ‘rescue’ them and deprive them of ‘agency’.

Over half the children also had some perspective for the future because they were saving money, either for themselves or their family. Even half of those who were not saving said they did not earn enough to save, and a little less than one-fourth did not know how to save. But aspirations to get a good job, wanting to learn a skill to be able to earn, and wishing to remain at the station because it provided the opportunity to survive, were scattered through the sample.

The stories of agency collected in the second phase give further clues into the deeper patterns underlying choices. They illustrated how the children responded to uncertainties by acquiring multiple identities in work and shelter distinct from that of ‘runaways’. A thrust for finding safety from harassment came across powerfully in the case studies, with many little tales of changing jobs, locations, trains, and even stations in search of safe havens to live and work in and plan for the future.

The children’s stories indicate harassment as a continuous state of being, marked by periodic episodes of violence. The police are seen as agents for extracting money out of the meager earnings of the children. Many of the care institutions, the NGOs, older children, passengers, and many others seem to be embroiled in the cycle of exploitation. The extent of violence to maintain relationships of power is a severe indictment of how care and protection are absent.

The main factor that enabled agency was the presence of friends at the station, although as often as not, the children were left fending for themselves. The case studies also point to another set of protective relationships with actual or adopted ‘relatives’ (uncles, aunties, didis and bhais), or with other workers at or outside the stations. The payment of protection money to the main harassers, the police, also figures in how children make decisions to continue to stay at the station.

A set of conclusions that emerge are that the majority of children are with families and not ‘runaways’, and their sense of ‘agency’, as well as ‘responsibility’ to the family, comes across strongly. The children also have a strong sense of living life on their own terms around themes of ‘fun’ and work, freedom from boredom and school, rebelling against parental control, liberation from long working hours, escape from caste taboos, or being financially independent.

The fundamental query the children pose is: why is working treated like a crime? They are persecuted by train passengers, by older children, family members, and even peers. And the culture of male persecution seems to have been internalised with those who have been persecuted in their childhood turning into persecutors themselves as they grow into adults; although there are also instances of mentoring, of a much richer tapestry of self-assertion and mutual cooperation.

Girls are differently located than boys both in terms of vulnerability as well as options. Age differentials also dictate what children can or cannot do. ‘Criminal’ activities pay more but that is offset by the costs to be paid for avoiding persecution. The railway station occupies a unique position around which many activities can be constructed – which is conditioned by the scope and safety it offers. And it is from this large canvas that some recommendations have emerged.

The recommendations are presented from the perspective of the children and their agency. They include key suggestions to the Railways to set up open or drop-in shelters, amend railway law, and set up a separate institution for participatory care and protection. For the Ministry of Women and Child Development, we propose the rescue-and-return paradigm be replaced by decentralised local bodies where the children can participate in designing and implementing preventive measures.

Major reforms are required in the various child-care institutions through re-training and re-orientation to look at alternative modes of care and protection. Consultation with children and their active associations is at the heart of this redesigning. Support has to be provided to the spirit of entrepreneurship and survival against odds displayed by the children with programmes for skill development, banking assistance, loans and credit lines, vocational education, and market support.

For CHILDLINE, and other organisations working with children, we recommend that they should critically examine their own experience, and link up with educational, vocational, skilling and financial assistance for protection and survival. They must also provide regular avenues for hearing the views of children (even on issues of sex and drugs) and to create platforms that would include these views in policy and practice, that do not depend only on punitive action.

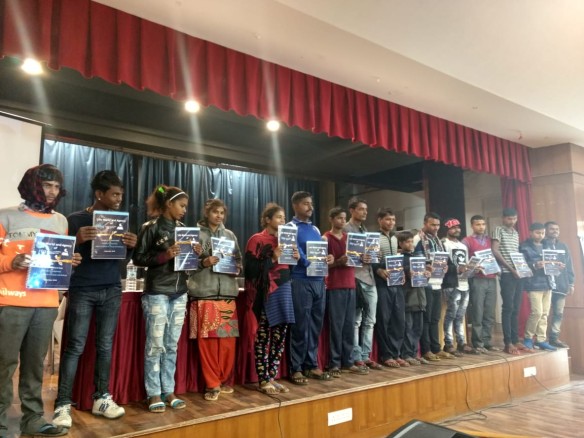

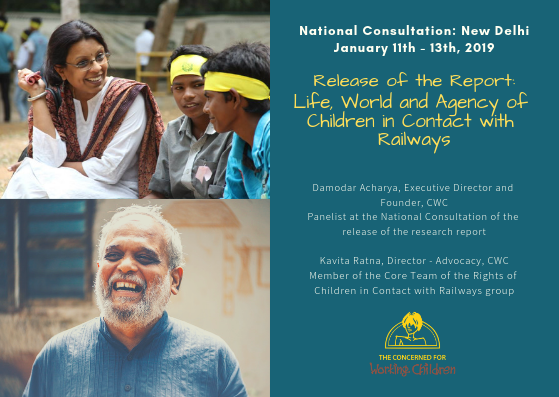

The report titled ‘Life World and Agency of Children in Contact with Railways’ was released on 12th January, 2019 at the National Consultation, New Delhi. Kavita Ratna, Director Advocacy of The Concerned for Working Children and a member of the core research team of the group ‘All India Working Group on the Rights of Children in Contact with Railways’ was present at the consultation to coordinate the discussion with some of the children participants at the event. Damodar Acharya, Executive Director and Founder of CWC was one of the panelists at the National Consultation.

Visit the website www.rccr.in to know more about the work by AIWG – RCCR with the children in contact with railways.

To read the full report, click here: RCCR_Report_2019

To read the presentation encompassing the key findings of the report, click here: RCCR Report PPT-3

Outlook: Railways must create a separate department for children found in premises: Study

Deccan Herald: Need separate department for children found in premises

Business Standard: Railways must create a separate department for children found in premises: Study