CWC Newsletter – Issue 11, April 2019

Young people and the 2019 General Elections

Nandana Reddy

With the 2019 election results expected on the 23rd of May, India’s fate hangs in balance. Will we save the largest and one of the oldest democracies in the world, or trade it for a dictatorship? Will we give in to the spectre of fear or choose freedom? Will our vote be for communalism or social harmony? War or peace? This has to be an informed choice. We need to sift through the rhetoric and to ‘think’. A faculty we are rapidly losing while turning into cyber sheep.

For some of us, the experience of a ‘state of emergency’ in India fifty years ago may jolt our memories and help us to recognise the features of fascism that have entered our lives. But only those of us above 60 may remember, not young Indians.

More than half the population of India is below 25 years of age and two-thirds, less than 35. These young men and women could be the deciding factor.

Addicted to their cell phones, many young people consider WhatsApp and Google as their source of knowledge. With the poor state of our education system, this has become the new ‘university’ of the young. It provides quick answers and instant gratification. Brains filled with unverified information, seeking social status through unknown ‘friends’ on Facebook and projecting a delusionary version of themselves, it gives them the feeling that they have arrived.

The promise of the internet was openness, transparency, togetherness, new communities, breaking boundaries of State, ethnicity and gender. 15 years later, we find it is a huge trap!

We have become slaves of technology and those who rule technology rule us. With money and resources, one can feed propaganda to the population through the internet. Divide through fear of terrorism and control through promises of ‘protection’. Rewrite history, distort facts, propagate lies, promote falsehoods. Brainwash and indoctrinate in the name of news. Anonymity hides the identity of the vile architect. Social media has become a new weapon in political armoury. How many will fall prey to this insidious conspiracy?

But young people are not a heterogeneous group. Our urban youth are ambitious, aspirational and impatient for change. What their NRI cousins think of India is more important than corruption or communalism – does not fit in here, at this stage of the article) To have smart airports with barriers that hide the slums en route and competing with the world’s biggest economies is more important than the plight of our farmers.

But there are also young people concerned about education that prepares one for a livelihood, safe jobs, good health care, protection for girls and a clean environment. These young voters are not taken in by issues of possible foreign aggression or the building of religious edifices. They are disgruntled, sceptical, cynical and frustrated. Angry at the failure of the state to deliver on its promises. They want a government that will listen and respond to their concerns. A government that will engage meaningfully with dissent. An establishment that represents them and not some obscure dogma. An administration that is democratic and not one led by an autocrat.

The Concerned for Working Children believes in nurturing in young people the natural instinct to question. Evolution, progress and invention would not have happened without this human characteristic. Why, how, when? We empower them to make informed decisions, using logic and real information to make choices. And most of all, discretionary use of the internet.

Namma Bhoomi prepares young people to be peaceful ambassadors of change. We equip them to build a democratic India from the bottom up.

India can’t progress if young people are deprived of this faculty. History has shown that slaves and sheep don’t a nation build.

Who will decide the 2019 elections? Slaves or questioning minds? Social media or those who have a vision beyond today?

Tearing apart the shroud of silence

Kavita Ratna

It was an absolute shock when late last year the news broke that about 100 boys were sexually abused over a period of 5 years, by the same man, in Udupi District. How did it come to pass that these violations had gone on across several locations and over so many years without detection? Why is it that the young boys who were living with their own families did not speak out or confide in anyone? Or did they confide and yet had been silenced? As in the case of most paedophiles, the man had entered into the boys’ sphere of trust by befriending their teachers and offering the children theatre classes and field excursions. If this ignominy had not been exposed as a result of medical treatment of an abused child, how much longer would these abuses have gone on?

It is significant that according to the police only 21 cases have been filed. The justification by the police is that they are proceeding only with those adolescents who they feel will be able to handle the rigours of investigations. This is also an admission by the police of the stark reality of our Juvenile Justice System which does not seem to have the capacity to engage with younger children with sensitivity.

The District Administration and the Police have become deeply invested in the matter now. The case is under investigation and the accused has been denied bail and is in custody while the wheels of inquiry are turning, slowly. In the recent past, one more incident of abuse of a boy has come to light; the accused is a member of the locally elected government and this time the response has been very speedy and decisive.

Children and their families who have stepped out to file complaints are being assisted by our organisation to access psychological counselling. This too required persuasion as the parents preferred to close the chapter shut rather than face the issue and trauma that the children are undergoing and address it. We are also holding discussions with all children and communities we work with, to channel the message that boys can be abused too.

The question still remains though as to why did claustrophobic silence last so long, even in communities where several support systems were in place? Is it because boys are considered safe? It has been noted that with adolescent girls becoming more aware of how to protect themselves the age of abused girls is dropping below 10 years of age. The perpetrators are stooping lower in search of more vulnerable girl victims. Are young boys now the easy prey?

As early as 2007, a study conducted by the Ministry of Women and Child Welfare, supported by United Nations Children’s Fund, Save the Children and Prayas, found 53.22% children faced one or more forms of sexual abuse; among them, the number of boys abused was 52.94% against 47 % girls. This is a staggering statistic. More than a decade ago, it challenged the practice of not taking into account male rape and sexual abuse, child or otherwise, as a crime.

Reporting on a study conducted in Kerala[1], and published in the Academic Medical Journal of India in 2014, Shyama Rajagopal writes[2]that that in a sample of 1,000 children of 13-16 years (512 boys and 488 girls), 38.67% boys and 37.7 % girls reported sexual abuse at some point in their life. This study incidentally was to probe into various behavioural changes, poor scholastic performance or suicidal tendencies reported by children who did not have a learning disability or Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) in a clinical setup. The findings then led to a full-fledged study on male child sexual abuse as most of the children who were harassed sexually, with or without contact, showed a traumatic change in behaviour. The study also showed that in most cases the perpetrator was known to the victim, 77%of the cases amongst boys and about 65% among girls.

Though this study covered only four southern districts of the state, similar results were obtained by Dr P. Krishnakumar[3], in a study[4]published in the Indian Journal of Pediatrics. Samples collected from across the state had indicated sexual abuse in 35 % girls and 36 % boys. Psychiatrists are also very concerned that sexual abuse in boys could lead to the perpetuation of the crime, that of creating a new perpetrator.

But to this day, the abuse of boys remains under wraps. As in the case of all sexual abuse, due to fear of re-victimization via the criminal justice system, reporting is a difficult decision to be made by the survivors and their caregivers. There is also a fear they may be blamed for the abuse itself, one way or the other.

InsiaDariwala’s petition on Change.org of 2018 has 1,23,740signatories urging the Ministry of Women and Child Development to conduct an in-depth study of male child sexual abuse. In her petition, Dariwal writes that it is quite unfortunate that while on one hand a girl’s sexual abuse is scorned and looked at as a serious crime while most men are pressurised by society to pass off their sexual abuse as a rite of passage. Sexual exploitation by older boys is often misinterpreted as sexual exploration and hence younger boys feel obligated to hide it. Many a time she mentions, that she has also come across people who refuse to believe that boys can get raped. Men are ridiculed and their sexual orientation is questioned and the pressure to live up to the façade of society’s macho image weighs in so heavy that ultimately the only way out, is to live a life within’.

The Minister of Women and Child Development Ms Maneka Gandhi stated that such a study would be carried out as ‘Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) is gender neutral. Boys who are sexually abused as children, spend a lifetime in silence because of the stigma and shame attached to male survivors speaking out. It is a serious problem and needs to be addressed. Despite the glaring statistics provided by multiple sources, including the Ministry itself, how does the government explain its total lack of response to the phenomenon of abuse of boys? To this day, even in a state like Karnataka where elaborate Child Protection Policies and Guidelines exist their application, in reality, is abysmal.

The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act is upheld as the State’s response. The abysmal prosecution rate under POCSO and denial of justice in numerous cases has come under severe condemnation. The rampant use of POCSO provisions to arrest and harass those under 18 years in consensual relationships has also come under criticism. So far POCSO has not been viewed as gender-neutral legislation.

In January of 2019, the government introduced amendments to the POCSO Act, which provides for death-penalty for aggravated sexual assault on children, making it gender neutral and introducing provisions against child pornography and for enhancing punishment for certain offences. The death penalty often contributes to lesser reporting because the abuser is often known to the family and there is a fear of retaliation.

Further, it is a contradiction to the reformist approach to law and justice. The Indian Penal Code, however, does not consider the fact that men too can be victims of sexual abuse. The IPC Sections 354A, 354B, 354 C and 354 D, dealing with sexual harassment, disrobing, stalking and voyeurism, all consider men as the perpetrators of crime, as in Section 375 of the IPC, which defines rape. This is also true of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, which also does not take into account the possibilities of men being victims of abuse.

Abuse of any kind is an expression of power imbalance and sexual abuse is among its most aggressive expression. It should not have been a surprise to know that young boys are abused in fairly large numbers. Despite the available statistics in public domain boys have long remained invisible in the gamut of sexual victimisation. They, like a large majority of children, lack the opportunities, scope and platforms for self-assertion and so children especially the younger children have become extremely vulnerable.

While the laws take their course, talking to mothers, fathers and caregivers in the communities, sharing their outrage, urging them to talk to their sons and young boys with candour about abuse is very important. Even more critical is to talk to young boys in every space possible and to create for them an environment where they can talk about themselves and their experiences. This would be crucial to help them see that abuse and bravado are not a part of being ‘men’. It would also enable them to look out for and protect each other just the way many girls have begun to do. Those guilty of committing the crime have to be punished and a message sent out that the time for the deafening silence against abuse of boys and girls is over.

[1]Study by Dr Arun B Nair, Department of Psychiatry and Dr Devika J, Department of Physiology, Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram

[2]Sexual abuse of boys goes under-reported, Shyama Rajagopal, September 10, 2014

[3]Director, Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences,

[4]Krishnakumar P, Satheesan K, Geeta MG, Sureshkumar K. Prevalence and spectrum of sexual abuse among adolescents in Kerala, South India. Indian J Pediatrics, 2014

Journey back home – Surviving a fragmented Juvenile Justice System!

Deepti Colaco

The journey of Babulal (name changed), a young resident of Namma Bhoomi (The Concerned for Working Children’s Regional Resource Center and Alternate Care Fit Institution under the JJA) to find his way back to his family is finally on the horizon. 5 long years after his departure from home, The Concerned for Working Children has successfully supported him to trace and re-establish links with his family in central Madhya Pradesh. Babulal is getting ready for his journey back home, to his mother and brothers, happy in the knowledge that they will welcome him back. He is now equipped with professional education in carpentry that he received while at the Concerned for Working Children. This journey back home may, however, throw up challenges related to his acceptance, assimilation in the community and his finding gainful employment in his hometown. He has been assured of continued support, whether he chooses to stay on or wishes to return to Karnataka for employment and self-sustainability.

This child who was found at the Udupi station in 2014 has been through the ill-functioning JJA system, somehow surviving its fault lines. During his interactions with the Child Welfare Committee, he was not provided with a non-threatening and empathetic environment where he could express his anxieties and talk about the home he had left behind in a fit of anger. Further given that he was in an alien and estranged environment and he may have not been able to express his views clearly, his right to be heard was not supported by enabling advocates. The sad reality is that Babulal is not an exception!

This is the plight of thousands of children in need of care and protection in the current juvenile justice system of India, where their right to be heard is constantly and unequivocally violated. The juvenile justice system under the JJA does not provide the children presented before the Child Welfare Committee the right to representation. The Concerned for Working Children has challenged the above and since 2010 and has been demanding for child rights friendly, legally informed representation to uphold the rights of the child.

While reviews have been carried out to inquire into the process and systems and to ensure that they factor in the views of children before the Child Welfare Committees, not much has changed over the years. In the exceptional occasions where children have managed to express their views, there is no system in place to ensure that the Child Welfare Committees give them due weight. In most cases, the Child Welfare Committees perceive that their role is complete once they institutionalise the children. Hence post institutionalization of the children, they disengage from them rather than facilitate the development of a long-term plan for the children that are in their best interest.

Children who are supposedly in need of care and protection do not even have the opportunity to express as to whether or not they require state protection. Often they are imposed with an unnecessary separation from their family. Children who come from situations of extreme vulnerability and may also have experienced neglect or abuse will need adequate support if they have to argue for their well-being, in a language that is alien to them, with adults who may seem intimidating.

Moreover, there are no uniform standards for the decisions that the Child Welfare Committees make and minimal records are maintained, leaving very little room for review. As a result, there is very little convergence between the Child Welfare Committees and the various agencies that are mandated to uphold the best interest of the child. This has been a problem from the very beginning of the formulation of the Juvenile Justice Act, wherein no formal standard operating procedures for implementing the policy were made to keep in mind the agency and experiences of children. This has left the juvenile justice system at the mercy of interpretations and will of individuals within it.

In the case of Babulal, after 5 years of him being in institutions, first in a reception home and later in Namma Bhoomi, he finally shared his desire to return back to his family and gave his family’s location. This was done with the support of the Concerned for Working Children staff. Instead of directing the responsible agencies such as the DCPUs, police, Child Line etc. to trace the family and to begin the process of restoring the child to his family, the Child Welfare Committee, placed the entire onus on the NGO partner. It was through invoking organisational contacts and persistent follow up of every single lead, that The Concerned for Working Children was able to ensure the support of the District Child Protection Unit, the Regional office of the Child Line, and the UNICEF office of the concerned state to find the child’s family and to establish contact with them. This points to a systemic failure of the JJA machinery and the lack of cooperation and collaboration among its various stakeholders. It also demonstrates the system’s lack of accountability to children and to the civil society. Further, this explains the huge number of children languishing in children’s homes instead of being part of their families or communities. The system and its functionaries, however, are let off scot-free for their transgressions instead of being held accountable for them

The violation of children’s right to representation and the lack of convergence between the various agencies mandated under the JJA to uphold the rights of all children coming under its purview repeatedly points to the urgent need to review and re-haul the current workings of the juvenile justice system. The Concerned for Working Children has raised these issues in since 2010 in dual submissions to the Karnataka State Commission for Protection of Child Rights (KSCPCR), and subsequently in 2012 through the amicus curiae to the suo-moto petition to the High Court of Karnataka.; In 2018 it made submissions to the JJA High Court Committee, thus utilizing judicial and civil instruments to highlight these concerns. The demand from The Concerned for Working Children is that continued proactive steps be undertaken by the system itself to infuse greater sensitivity towards these children, and to develop a more approachable method that supports the children to be directly or indirectly heard in decisions that will change the course of their lives.

It is every child’s constitutional and fundamental right that when in need of care and protection they must be given assistance, either through civil representatives or through legal representation by those who have the resources and expertise for working with children

Further, minimum standard procedures have to be developed to facilitate proactive and sensitive action from all responsible agencies to ensure the speedy and effective resolution of cases pending in the Juvenile Justice System.

The above recommendations are just starting points to reform a currently ailing system of juvenile justice. However, the call for change has to begin and begin strongly to ensure that we as a society and the system that we as citizens are supporting, stands up, takes onus, and ensures that more Babulal’s do not perish in the cracks of the Juvenile Justice System.

Deepti Colaco

—–

To read more about the Suo Moto Petition submitted to the High Court of Karnataka, click here: Amecus report (SUOMOTO petition)submitted on _JJ 20-6-2012 to highcourt

To read more about our submissions to the High Court Committee on the Juvenile Justice Act, click here: 4&5Juvenile Justice In Karnataka A Case for Systemic Change-The CWC

To read more about Namma Bhoomi, click here

To read more about Namma Nalanda Vidhya Peetha, click here

To read more about the Udupi District Child Protection Protocol, CWC and the Udupi District administration’s strategic initiatives to systematize convergence, click here

Please do visit our Website and Facebook page for in-depth discourse on these and other issues.

Sharing the highlights from the first quarter of 2019

Nishita Khajane

Members of Bhima Sangha come together to observe the National Child Labour Day on April 30th, 2019

Nearly 50 members of Bhima Sangha from Annasandrapalya, Vigyannagar and Nagavarapalya, participated in the celebration of the National Child Labour Day held at the office of The Concerned for Working Children today. They watched Swarabhoota and Mangana Upavasa, films from the Makkala Toofan series. Children also had a chance to revisit the Bhima Sangha history and understood the significance of the collective.

With the rise in cases of abuse of children, especially male children, information was shared with children to guard themselves and be aware of abusers, who tend to target both boys and girls. Members of Bhima Sangha also observed the day at Huvinahadagali taluk, Bellary district, where they received information about the support and help they can seek from Makkala Mitras (Children’s Friend) and Mahila Mitras (Women’s Friend) and about the recent amendments to the Prevention of Child Marriage Act, Karnataka. To read more about the day, click here.

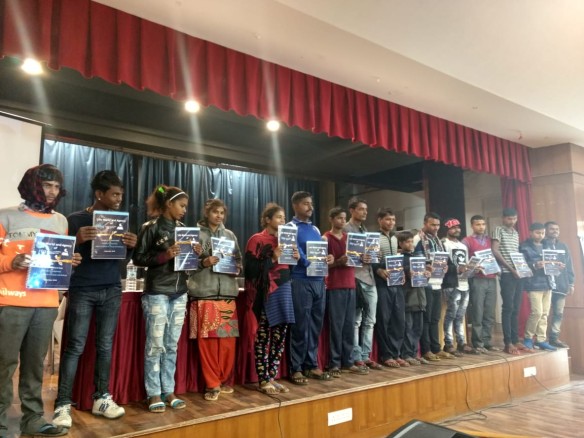

Bhima Sangha, Karnataka and Grama Panchayat Hakkottaya Andolana release manifestos ahead of the general elections 2019!

Bhima Sangha is a union of working children advocating for the rights of working children across Karnataka, since 1990. The members of Bhima Sangha are active in Bangalore, Udupi and Bellary districts. More than 60 representatives have come together (Facilitation of the process: The Concerned for Working Children) to put forward their manifesto to the candidates contesting in the upcoming general elections 2019. Those that have a genuine interest in upholding the well-being of children must consider this manifesto with great seriousness and importance.

The Grama Panchayat Hakkottaya Andolana releases its manifesto today, looking forward to aspects that enable strengthening local-governance institutions towards functioning as local self-government in the manifestos of national political parties. The candidates contesting in the general elections 2019 must uphold the interests of representatives of the local self-government, members of the gram panchayats and the general public in the rural areas to progress towards strengthening decentralized democracy. GPHA also wishes to highlight that the implementation of any public welfare schemes can be successful only if decentralization exists in its full spirit.

To read more about the release of the Bhima Sangha and the GPHA manifesto, click here.

Me & My VOTE are NOT for SALE campaign reaches nearly 40,000 people across the country ahead of the general elections 2019!

The ME AND MY VOTE ARE NOT FOR SALE campaign celebrates the honour of the voter. It empowers each one of us as citizens to reclaim democracy. From its launch in the 2010 gram panchayat elections, the campaign has achieved several milestones. The powerful campaign, spearheaded by Grama Panchayat Hakkottaya Andolana (GPHA), of which CWC is the secretariat, takes on clarion call that WE, the CITIZENS and the VOTERS have the power to effect change if we vote with integrity – keeping at the forefront rights, development, and social justice to all in the nation. The campaign takes a bottom-up approach by reaching out to those who have often been forgotten: the marginalized groups, rural populations, women, and youth.

Keeping with the national elections 2019, the campaign has reached close to 40,000 people across the country through various communication mediums. It has specifically focused the youth and women, keeping in mind their presence among the larger voting population and also as a result of the strong faith in these groups to uphold democratic values and bring about change. The campaign has spanned across several districts of Karnataka such as Kolar, Chikkaballapur, Chitradurga, Bidar, Yadgir, Mysore, Ramanagara, Belgaum, Tumkur, Raichur, Bijapur, Koppal, Davangere, Gulbarga, Udupi, Bangalore and Bellary. This has been possible as a result of successful collaborations with organisations such as Bangalore Rural Educational And Development Society (BREADS) Bangalore, Rotaract Club of Rotary District 3190, The Association of People with Disability (APD), Ondede: Dignity – Voice – Sexuality, Sanchalana, Belaku, Jagruthi Mahila Okkuta and the Association for Promoting Social Action (APSA) and several colleges and universities to help us spread the message to the persons with disabilities, LGBTQ and other communities and civil society groups that they work with. Under the Child Rights Education and Action Movement (CREAM) Programme, BREADS, the campaign has reached several MGNREGA workers and communities. In association with APD, the campaign has been able to reach several groups of persons with disabilities across Karnataka.

GPHA has also collaborated with the SVEEP programme of Udupi and Bellary districts and conducted awareness campaigns with the general public. Several sellers and buyers at weekly markets held at Kundapur and Udupi taluks and interaction with fisherman at the daily fish market at Malpe, Udupi and the dwellers of migrant settlements in Udupi district, have extended their solidarity to the campaign by wearing badges, pasting the sticker ‘Me & My VOTE are NOT for SALE’ on their trucks, cars, bikes, weighing scales, vegetable baskets, doors and walls of their homes. They have even put up posters showcasing interesting slogans like ‘Vegetables are for Sale but NOT our Votes!’

Read more about the overview of the campaign here. You can also find the link to the full press release here. You can also follow our campaign on Facebook and Instagram.

Admissions Open at Namma Nalanda Vidya Peetha for 2019 – 2020 batch!

Namma Nalanda Vidya Peetha (NNVP) is the school inspired by the principles of Montessori that emphasise freedom with responsibility, which respect a child’s natural psychological development, founded by CWC. NNVP calls for applications for its vocational courses for the academic year of 2019 – 2020! Various short term vocational courses are being offered to children from highly underprivileged and marginalized backgrounds, coming from difficult circumstances. Courses such as Tailoring, Embroidery, Plumbing, Electrical, Beautician and Carpentry are being offered. Children are also exposed to holistic development learning opportunities such as life skills, art and theatre and also get an opportunity to hone and display their talents. Child-friendly residential facilities along with nutritious food will be provided to the children. For more details about the courses offered, read our pamphlet here.

Representatives of migrant communities meet with the District Commissioner, Udupi district to claim their entitlements as a follow up to the state-level convention of the migrant labourers’ union

Nearly 60 members of the Migrant Labourers’ Union, facilitated by The Concerned for Working Children, met with the District Commissioner of Udupi District, Smt. Priyanka Mary Francis on 8th January, 2019, to raise several issues faced by the migrant communities dwelling in Udupi district such as providing housing facilities, street lights, issuing identity cards such as ration cards and voter IDs for the migrant and the fishing communities, drinking water, toilets, scholarships to children, providing cooking gas, regular beat by the police to ensure safety and protection and proper documentation acknowledging their presence. The District Commissioner has ensured that their issues will be addressed. To read more about the convention, click here.

Integrated Child Protection Services Scheme (ICPS) endorses the Udupi district Child Rights Protection Protocol as a model to Karnataka

The Concerned for Working Children had the opportunity to share with more than 300 representatives of 30 districts of Karnataka of the Department of Women and Child Welfare, regarding the Udupi district Child Rights Protection Protocol, through video conferencing mode in a sharing session organised by the Integrated Child Protection Services Scheme department, Government of Karnataka.

The Child Rights Friendly Protection Protocol (CRPP) of Udupi district is a comprehensive and a one of its kind policy developed to ensure that all children receive care and protection. The protocol, through various mechanisms to strengthen children’s participation, has enabled children to interface directly with policymakers, officials and representatives from the district level to the local government and to ensure the accountability of the government at all levels to the children.

The districts had come together to share ‘good practices’ that they had adopted with the safety and protection of women and children. Representatives of Bagalkot, Hassan and Madikeri districts expressed their interest in replicating the models in their respective districts. Our team also had the opportunity to share with them regarding the Me & My VOTE are NOT for SALE campaign and its reach throughout the state of Karnataka.

Get a glimpse of the Udupi District Child Rights Protection Protocol here.

Read about how CWC has collaborated with the Udupi District administration to create a child rights friendly Udupi district here.

To read about the release of the Udupi District Child Rights Protection Protocol, click here.

Read the Udupi District Child Rights Protection Protocol in English here: UdupiDistrictChildRightsProtectionProtocol2018_English

Read the Udupi District Child Rights Protection Protocol in Kannada here: UdupiDistrictChildRightsProtectionProtocol2018_Kannada

Life, World and Agency of Children in Contact with Railways: A report by AIWG-RCCR

The report titled ‘Life World and Agency of Children in Contact with Railways’, was released at the National Consultation, New Delhi. The session, where children and adolescents in contact with railways spoke about their concerns, the abuse they have gone through and their aspirations, was facilitated by Kavita Ratna, Director Advocacy of The Concerned for Working Children, who is a member of the core research team of the ‘All India Working Group on the Rights of Children in Contact with Railways’ (AIWG-RCCR). Damodar Acharya, Executive Director and Founder of CWC was one of the panelists at the National Consultation, where he talked about the history of ‘agency’ of working children, tracing the trajectory of the Bhima Sangha, facilitated by CWC for close to three decades and suggesting strategies for way ahead. The report is available on the website www.rccr.in.

To read more about the report and the national consultation, click here.

CWC’s response to the Madras High Court’s judgment regarding a recent POCSO case

The Concerned for Working Children welcomes the judgment by the Madras High Court dated 26th April 2019 with respect to the case of Sabarivasan v/s Tamil Nadu State Commission for the Protection of Child Rights and others, that impressed upon the need to insulate physical relationships between teenagers due to infatuation or innocence from the draconian provisions of the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act of 2012. This is a welcome judgment that highlights the loopholes in the POSCO Act that is meant to uphold the ‘Right to Protection’ of children as held by the UNCRC. To read the complete response, click here.