CWC Newsletter – Issue 6 July 2015

- Have we asked the children?

- ‘Banned-aid’- Coming soon!

- Critical research & writing on child rights

- Recent news

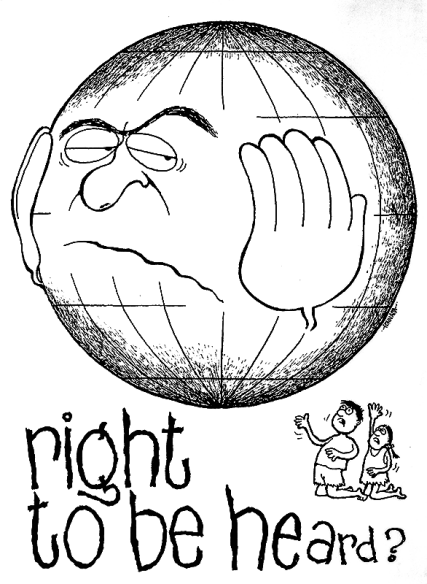

Have we asked the children?

The child’s ‘right to be heard’ has been validated by a UN Convention. It’s time to let children decide when and what kind of labour is right.

The debate over children working has been raging for centuries, with policies constantly changing to reflect the attitudes of a given time. During the World Wars, children were allowed to work as they were needed in factories and other services. When the soldiers returned home to their jobs, the children were packed off again to schools.

There are different views in society about why children should or should not work. Rationalists see the need for children to work in poverty-stricken countries and close their eyes to the oppressive and often hazardous conditions under which they work. Moralists, with their ‘good intentions’, want to ban all work for children to enable them to enjoy their childhood, regardless of the conditions they face at home. Economists see children as contributing to the Gross Domestic Product of the nation’s economy. Politicians, especially those who want to be seen as ‘progressive’ and their countries to be listed as ‘developed’, make compromises between what is convenient for industry to flourish and what is feasible to implement.

Nothing without their consent

But few of these groups bother to ask the children themselves what they want. Children are thinking beings who know what they like and dislike and, depending on their age and ability, also most often know what the solutions are to particular problems they face. Children’s ‘right to be heard’ has been validated by the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child that India has ratified. Twenty five years ago, Bhima Sangha, a union of, by and for working children was formed to draw attention to working children’s concerns. It strongly upheld that no policy or decision regarding children’s present or future should be taken without their consent. In 1996, Bhima Sangha, with the support of the International Working Group on Child Labour (of which The Concerned for Working Children was a member), held the first International Meeting of Working Children in Kundapura, Karnataka.

On this historic occasion, the International Movement of Working Children adopted the Kundapur Declaration drafted by working children from 36 countries. They demanded of states and international agencies that they be consulted, their initiatives recognised, and their products not boycotted; that their work be respected and made safe; that they have access to appropriate education, professional training and quality healthcare; that poverty be addressed aggressively; that rural development to stem rural-urban migration be made a priority; and, importantly, that exploitation of their labour be brought to a halt. These issues, listed in the Declaration they signed, are highlighted every year on Child Labour Day (April 30). There is also an Anti Child Labour Day, celebrated on June 12. On this day, national and international agencies highlight their objective to eradicate child labour through ‘raid and rescue’ operations that have now become standard operating procedure for the entire spectrum of child work, ranging from the intolerable to the enabling. To this working children ask, “Do they want to eradicate us like pests using pesticide? Are we not human beings with rights that deserve respect?”

Phoney facelifts

We always seem to get the wrong end of the stick. Instead of understanding the working children’s demand for rural development and poverty eradication, we have perpetuated poverty with sops in the form of one rupee rice and Below Poverty Line cards. When inclusive development should be our priority, we focus on phoney facelifts.

When one in three Indians lives below the poverty line and 46 per cent of India’s children are malnourished, any legislation has to be an enabling one. We know from historical experience that legislation cannot be enforced without a dramatic change in people’s lives.

For instance, the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 has been in force for almost 30 years; yet there are a large number of working children. The Child Labour Programme (CLP) has been renewed, with minor changes, several times over the years, irrespective of the fact that the rate of convictions for employing children is dismal and little is being done to mitigate the plight of children in the workforce.

Instead of analysing the root causes of child labour, we have continued with an ostrich-like approach. An example of this is the recent proposed amendments to the Child Labour Act of 1986. Even though it recognises that work can also be a learning arena for children, and that socio-economic conditions are the root cause of child labour, which is a step in the right direction, the amendments it proposes ignore these insights. They instead take the line of least resistance and relax the ban on children working in family-owned occupations, a sector that is informal and very difficult to monitor, given that the labour machinery does not extend that far. This will also encourage caste-based occupations. The most dangerous possibility is that the industry will use this loophole to use ‘families’ for production.

Relaxing the ban in the entertainment industry, one of the most exploitative industries in the world and riddled with sexual abuse, appears like a concession to the advertising sector, which is using children as a selling gimmick for all kinds of products.

Instead, what should have been suggested are safe and strongly protected occupations in the formal sector, which are part-time and can be easily monitored. The proposed amendments also extend the ban from children below 14 years to include children below 18, thus extending criminalisation as well. Instead, they should have explored the Apprenticeship Act, and provided ‘earn as you learn’ avenues for children in this age group, as countries such as Zimbabwe and Norway have done.

The proposed amendments are a setback — mere minor tinkering of an already faulty approach. What is required is an approach that focuses on children’s rights and which addresses the causes of child labour, primarily poverty. Yet, the proponents of the total ban persist in their simplistic equations and draconian strategies. Manju, a working child, summed it up. Describing the efforts to eradicate child labour, he said that the children were like a pot of boiling rice and the child labour policies just kept scooping away the froth from the top. What is needed, he said, is “to remove the fire below”.

Source: Nandana Reddy. (June 13th, 2015). Have we Asked the Children?. The Hindu. Accessed from: http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/have-we-asked-the-children/article7310187.ece

‘Banned-aid’: Coming soon!

Why do children work? How has the current child labour law, articulated through the partial ban, affected them? What happens to children during raids and after they are ‘rescued’ by the government? The docu-drama entitled ‘Banned-aid’ is a collaboration with members of the Bhima Sangha (Union of Working Children) to explore and respond to some of such important questions which currently remain unanswered. The stories shared are real incidents as experienced by working children themselves. The enactment and voice-over have also been undertaken by the sangha members. The docu-drama gives an important insight into why listening to children is a non-negotiable to address child labour in the long-term.

Critical research and writing on child rights

A. Unicef. (2015). Progress for Children. Beyond Averages: Learning from the MDGs. New York: UNICEF.

“The MDGs provided countries with direction – purpose – and a 1990 baseline against which to measure success. But in many cases, measuring global averages masked differences at regional, national and subnational levels. And so, despite achievements during the MDG period, millions of the most disadvantaged children are being left behind – partly because without concerted efforts to track different results for different groups, inequities can go unnoticed.”

‘Progress for Children’ evaluates the Millennium Development Goals with a focus on children. The report presents data and elaborates how the MDG’s had a positive effect on the lives of children such as, child survival, nutrition, HIV, primary school enrolment, alongside studying the limits of the MDG’s. Unicef argues that despite the achievements of the MDG’s, the most marginalised children have been left behind. For the development of the new development agenda, Unicef emphasises how more data is needed on marginalised children who are often hardest to reach. When the most marginalised are covered in data collection, Unicef states that ‘every child will be guaranteed a voice’.

B. Howard, N. (2014, November 6th). On Bolivia’s new child labour law. Open Democracy.

“But I want readers to see that in our unjust, unequal and unfair world, regulating child work is better for working children than the counter-productive sticky plaster of abolition. Instead of condemning Morales as regressive, abolitionists and their allies would do better to marshal their forces against the wealth inequalities that necessitate child work in the first place.”

Bolivia recently lowered the working age for children to 10 with conditions. This decision created much upheaval in Bolivia and across the world. International agencies such as UNICEF, ILO and other child rights organisations – came out strongly against such a law. Neil Howard argues through his article why it is in the children’s best interest to formalise and regulate child work. According to Howard the law is a progressive step in the right direction.

“The report is produced in a context, which in recent years has given rise to increased focus on collaboration and cooperation amongst countries of the South Asia Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), focusing on the challenges they face and the possibilities for maximizing opportunities. Child labour is among these issues.”

The report brings together data from national household surveys of eight South Asian countries –Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal, the Maldives, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, and maps nature and extent of child labour, children in employment and the relation between education and employment. According to the report 16,7 million children between 5-17 years old are in child labour, where most children work in agriculture. Work has a negative effect on the education of children. The report makes four main recommendations. Firstly, a strategy that embeds the responsibility for and response to child labour into the work of all institutions, initiatives and partnerships that can make a difference. Secondly, it adopts the life-cycle and inter-generational approach to evaluate and approach child labour. Thirdly, it argues for a higher spending on education. Lastly, the report emphasises the need for more qualitative data on child labour.

Recent news

- ‘53 per cent increase in child labour’

- How we can help girls and boys who combine school and work

- ‘A justice system that fails children ultimately fails society, ‘ UN right expert warns

- Over 8000 children work in Delhi’s garment sector