A Mother’s Sneha [Love]

Posted on June 29, 2015

Excerpts of this article have been published in The Hindu, June 2015.

A Memory Montage of My Mother

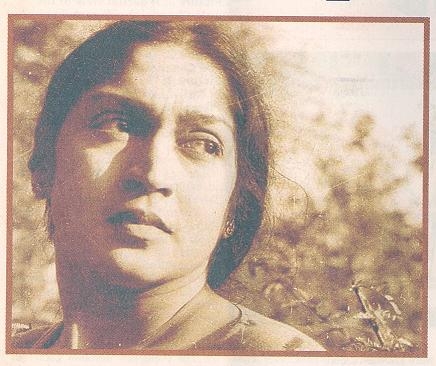

Snehalata Reddy was incarcerated in the Bangalore Central Jail during the State of Emergency declared by Mrs. Indira Gandhi, first under Defence of India Rules and then under Maintenance of Internal Security Act with no hearing, no charges filed and no recourse to a court of law. She died on the 20th January 1977 before the Emergency was lifted. She was an artist, actor and political activist.

The sudden ringing of the phone rips the silence and snaps me out of my reverie. I rush down the stairs to the dining room hoping it won’t stop before I reach. It is a land line [there were no mobile phones those days]. I snatch the receiver off the set. I hear my mother’s disembodied voice. “They have brought me here again, can you come?” I rush to our shabby Fiat and reverse out of the ziz zag driveway in one single motion till I hit Saint Marks Road and then race to the Victoria Hospital. Dodging traffic I pray I get there in time – before they take her away.

These images continue to haunt me after 40 years. I still wake up in a sweat to the ringing of that phone. I am still trying to compensate for the madness of the Emergency. I can never compensate for losing her so soon, so young, so pointlessly and am still trying to understand why and to put things right by assuaging my anger with constructive actions. As if by doing so, I can bring her back or fulfil her aspirations. And each day, I realise how miserably I fail. And now with a cultist authoritarian Prime Minister the old fears resurface.

I find her, as always, sitting in the RMO’s room having an animated discussion about public health and the care of female prison inmates. She turns to me, almost regal in her bearing, but there is pain and sadness in her beautiful eyes. We hug and kiss wordlessly. I cling to her for a moment – almost believing that if I hold her tight enough they can never separate us.

The RMO advises hospitalisation. Her asthma attacks have become more severe and her lungs are weak. She is self administering Adeline injections in jail as the jail doctor cannot be bothered to come at all hours of the night. She has gone into an asthmatic coma twice. The orderly is asked to bring the forms and the RMO begins filling them in. We hold our breath, hoping that this time he will succeed in admitting her. Just as we feel we are home-safe, the call comes. The Home Secretary refuses to allow the admission. The RMO stutters an apology. He cannot look us in the eye. He mutters some explanation and promises to follow this up. As compensation he suggests that we go into an anti room so we can have a few moments alone together.

We sit looking at each other, examining every feature. I study every wrinkle, the mole on her lip, the kumkum on her forehead – I look for signs of hope. Our eyes speak a different language while we talk of mundane things. Does she need anything? Is my brother ok? How is my father coping? Who washes her clothes? What about the food? Does she have enough medication?

Time is up. We hug hurriedly whispering “I love you”. The police have come to escort her back. I feel limp and helpless as I watch her being led away to the police van. The doors shut and I can barely see her through the grill. Our eyes are locked. I follow the van through the streets of Bangalore to the Central Jail. The large almost fortress like doors open with a loud grating metallic echo followed by a deafening thud as they hit the inner walls. The van drives in – I lift my hand to wave – she does the same – our hands freeze in mid wave till the doors shut with a final bang. I stare at nothing for a long while following her with my mind. The body search. The long walk to the cell. The clang as the cell door shuts. The rattle of keys. The shrill laugh of the warden. She is sitting defeated on her cot. The tears began to roll uncontrollably. She is so near – yet so far away!

Snehalatha Reddy or Sneha, as she was affectionately called was born to Indian Christian parents – second generation converts. Her maternal grandmother was a Kashmiri Brahmin married to a Bengali Brahmin. Her paternal grandparents were Tamil Mudaliyar’s and her father served as a Major in the British Army. As my grandparents did not speak each other’s mother tongue, English was the language spoken at home, were anglicised and all the children were given English first names. My mother resented the British and all that came with Colonial Rule, so when she went to college, she reverted to her Indian name, wore only Indian clothes and a large bottu. She learnt Bharatnatyam from the renowned Sri Kittappa Pillai and became a very accomplished dancer.

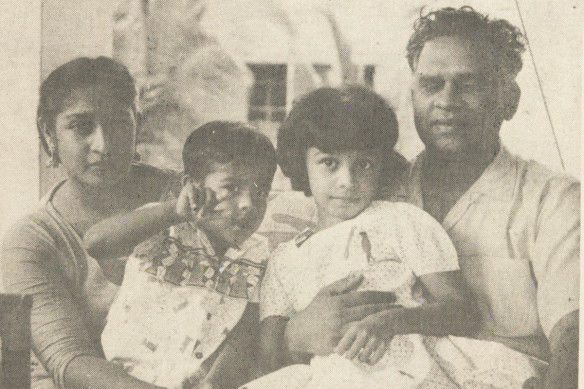

My father Pattabhirama Reddy saw her dancing at a Queens Mary’s College event where she was a student and it was love at first sight. She was stunningly beautiful and feisty at the same time. My father vowed not to shave until he had made her his wife. My father came from a wealthy landowning traditional Hindu family who were freedom fighters, anti British and staunch supporters of Mahatma Gandhi. However, my father’s decision to marry an Indian Christian met with strong disapproval and my Grandfather refused to even see my father informing the family that they should consider him dead. My father was disowned and financially cut off. After an Arya Samaj wedding witnessed by loving friends, my parents began their life in a small shack on the Adayar Beach.

We have just sold the months newspapers and have decided to have a family treat. We go to the drive-in Woodlands near Gemini Circle in Madras. I am 5 years old and feeling a little insecure about our finances. She tells us that she has a magic box full of money that is hidden away in a secret place and if we ever run out of money we can go and get it. She asks me if we should get it now and I say no, already feeling safe. I eat my puri pallya and think of other things.

My mother could spin magic. She could turn gloom into sunshine and turn fear into the excitement of adventure. She had a tormented childhood and understood my anxieties. When she was a child she defended her siblings from her parents thrashing and she was determined to spare us such trauma. She was a born human rights activist. She opposed cruelty in all forms. She defended her classmates against discrimination in school, stood up for the downtrodden and all her life fought for the freedom and rights of women and the marginalised.

We find a notebook among her meagre possessions. In it she has scribbled her feeling and perceptions – the events that occurred in the women’s ward of Bangalore Central Jail. On June 1976 she wrote; “As soon as a woman comes in she is stripped naked in front of everyone else. When a human being is sentenced, he or she is punished enough. Must the human body be degraded and humiliated as well? Who is responsible for these perverse methods? Shouldn’t intelligent Superintendents, IG of Prisons etc go on improving conditions? What is the purpose of every human being born in this world? Is it not to lift mankind a little higher towards perfection? No matter which walk of life a human being is born, his mission is to raise standards in human feelings and thoughts in every possible way.”

These are the principles she set for herself and for us all, especially my brother and I. My relationship with her was complicated – she was the most caring mother, addressing all my concerns and making sure that my formative years were unique in every way. Every birthday was a special occasion. For my first birthday she filled our courtyard with balloons and made me a ballerina frock, another one was a carnival and yet another, a Spanish restaurant complete with Spanish food and a guitarist! Yet at the same time her expectations of me were very high. She would not condone any breech of the family moral code and as I imbibed these values I too like her became a champion of human rights at a very early age.

On June 9th 1976 she wrote; “At least I have achieved something here. I have stopped the horrible beatings the women prisoners used to get. The food has slightly improved for them. And though the water supply is appalling, yet there are promises for pipes to be connected and that is not bad at all. And most of all, I have made them unafraid a little. I went on a hunger strike till the food improved slightly.”

Things began to deteriorate in India in the 70’s. Though Indira Gandhi was on the crest of popularity after winning the 1971 war against Pakistan, and the explosion of a nuclear device boosted her reputation as a bold and shrewd political leader, by 1973, the whole of North India was rocked by movements and protests against high inflation, the poor state of the economy, corruption, and the low standards of living. In June 1975, the High Court of Allahabad found Mrs. Gandhi guilty of using illegal practices during the previous election and ordered her to vacate her post as prime minister. There were demands for her resignation from around the country and finding that there was no other way to resume power, Mrs. Gandhi declared the State of Internal Emergency.

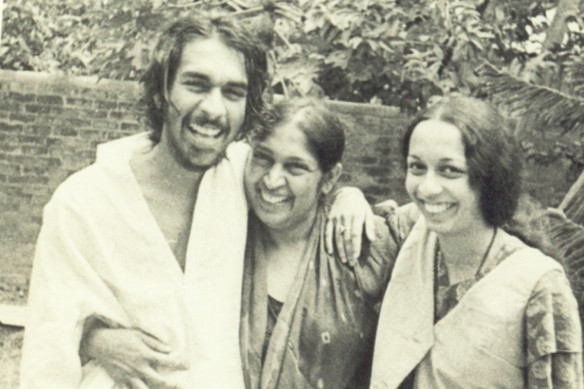

It is June 26th 1975. The Indian State of Emergency is announced. It is also the last day of shooting of the film Chanda Marutha [Wild Wind]. My parents have sensed this coming and Chanda Marutha is a prediction of things to come. George Fernandes is in hiding and comes to Bangalore with a proposal to start an underground movement. I am sitting on the wall outside his hideout listening to my mother vehemently arguing for a non-violent movement while George makes a case for selective violence. I want to do something and I have volunteered to join the movement. My mother is afraid for my safety, yet grudgingly agrees as she understands that I have to discharge my political obligations in keeping with my beliefs. After all she has taught us well and understands that we cannot be mere bystanders when our constitutional freedoms are being denied.

My Mother was an artist, an actor, dancer and activist. She was the outward gregarious person who loved people and abhorred injustice, while my father was more reflective, the strong voice of reason, the tranquil revolutionary. She was passionate and warm and he was calm and empathetic. He engulfed her with his love, gave her a safe harbour to anchor and supported her in all she did. As one of our close friends Lakshmi Krishnamurthy said; “he was the shade that protected her flame”.

My mother was a passionate crusader of human rights and would intervene without a second thought. She was famous for stopping in the middle of the road to protect a beggar from the harassment of a policeman, or taking a school principal to task for victimising a student, or chastising a husband for persecuting his wife. My father would support her silently through these interventions and offer calming advice. My parents shared a rich partnership based on mutual love and respect, filled with idealism.

My father is shooting Sringara Masa [Paper Boats] while my mother is in jail. A film about a couple who are trying to rebuild a relationship that has broken down – a film about the rekindling of love, the rebuilding of trust and the renewal of friendship. This is a film they were to make together but the Emergency and her detention have prevented that. My father is persuaded by her to go ahead and my mother assists him from jail. She writes notes to the actors and when we visit twice a week my father updates her and they discuss and plan the finer points of the film. This film becomes my father’s offering to my mother. It becomes a virtual world in which they partner. It is an escape from the reality of separation and confinement of the four grey walls of the prison. For us it is a means of living her dream.

She was a marvellous Actress, one of the best I have seen. She became the part she was playing, totally absorbed in the character, imbibing the emotions, mannerisms and posture until the character came alive through her. As a result there was nothing false in her portrayal, nothing put on, no false note. She would practice her lines incessantly at home and I would help her. There were times during these periods of preparation that she would suddenly switch into character leaving us rather bewildered. Theatre and film were a part of our lives and that is probably why I can still recite long passages from Chekov, Shakespeare, Pinter and Arthur Miller.

I can still remember watching her play the mother in Ibsen’s Peer Gynt directed by the internationally renowned Peter Coe when I was about 8 years old. It was a stunning performance. On stage she was Ase, the Norwegian widowed peasant, mother of Peer Gynt with no resemblance to my mother.

She is lying on her cot, her hair is grey and her face is lined with wrinkles. There is pain in her eyes and her movements are feeble. Her son is sitting by her bed and recounting a trip they made by horse carriage. She groans and her son bends down and shifts her into a more comfortable position. “There, that is better”; he says. “I want to get away”; she says.”It is what I’m always longing.” He tells her not to talk like that and tries to divert her attention. He moves to the foot of the bed, throws a cord round the back of the chair, takes a stick in his hand and pretends that he is driving the horse carriage. He knows she is dying.

He says; “To Soria-Moria Castle, that’s westward of the moon and eastward of the sunrise, they’re having a splendid feast. Rest back upon the cushions; I’ll drive you quickly there.” She asks if she is invited and he says; “Of course and I am, too.” She hears a hollow sighing sound, she is afraid. He says it is just the trees whispering on the hillside. She sees a light in the distance. He says they are the lights of the castle; swarms of people are waiting to welcome her in. She shuts her eyes and lies back with a final sigh. She is no more. There is pin drop silence and then the auditorium bursts into resounding applause.

My mother had a special bond with my brother Konarak. When my parents were on their honeymoon in Spain my mother learnt Flamenco Dancing and she dreamed of having a son who would play the Flamenco Guitar. When my brother was born he took to music instinctively, as if he was destined to do so. He was the fulfillment of her dreams.

August 16th 1976 my mother wrote. “Peace today for everyone. No Head Warden. But for me there is pain and hunger in my soul – I want my son! I need to see him, speak to him so much, so very much – to be with him these last few days. My son is going away. I will meet a man next time. I will have to search for the boy in him. How will it be? When will I see him? Why this pain for me alone? Why?”

My mother wanted my brother to escape all this madness and forced him to accept a seat in Berklee College of Music, Boston, USA. He took leave of her in jail. They both had a premonition that they would not see each other again. In a final farewell, my brother bent down and touched her feet – something we never did.

Both my parents were Socialists and greatly influenced by Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia. Though they expressed themselves through the arts political activism was their foundation. Their political ideology permeated their lives and their art. So when Shantaveri Gopal Gowda suggested that my parents read UR Ananthamurthy’s Samskara, the brilliant and thought provoking novel that questions the very basis of religious dogma, they instantly decided to make it into a film. They plunged into the project even though they had no money.

The making of Samskara was a convergence of diverse people from diverse disciplines. The film brought journalists, theatre persons, socialists, main stream film technicians and lay persons together. It was perhaps the first time when my parents’ political beliefs and their creative talents found a common outlet.

She has just bathed in the river Tunga and is drying her sari. Praneshacharya walks past after his bath. She turns her head and follows him as he walks up the bank. Her eyes are liquid with unshed tears. Her gaze is expectant and craving an answer – she longs for closure.

My mother’s portrayal of Chandri was poignant and magnetic. With practically no dialogue she conveyed the emotional complexity of a Devadasi woman who has lost her Brahmin lover; the dilemma of a woman witnessing an inconclusive discussion regarding his cremation; and her unexpected response to Praneshacharya’s need for comfort. The alienation created by caste and her isolation for breaking this rigid hierarchy.

My mother always paid scant respect to caste and class. Her friends were socialists, artists, writers, young people, men and women of the working class and just ordinary humanbeings. It was her endeavour to bring people together. People who otherwise never spoke to each and who would not even want to be seen together met at our home, shared ideas and food. She was an incredible cook and loved to feed people. No one left home without a meal or at least a cup of tea. We would eat Bengali, Tamil, Andhra, Italian, Spanish and Chinese; Moroccan and Turkish, Egyptian and Balinese cuisine. And each of these meals was a journey into that country.

I am sitting perched on a stool watching my mother cook. She is explaining each step in the process, describing the ingredients and telling me about the country and the people where the dish originated. Her face is animated as she speaks with the accent of those people. I giggle as she wipes her forehead with the pallu of her sari. I can smell the aromas and my mouth is watering. I can see the land from which it has come and hear the people. I want to go there and she promises that we will one day.

That day never came. I was never able to travel with her. Almost all my travels were after she had passed away. Though her travels were confined to a brief period just before I was born, my mother was cosmopolitan to the core. She had no national boundaries and harboured no discrimination. She was open to ideas and influences from all over the world and from all walks of life. She imbibed in us this ability to openly embrace cultures, languages, food and most of all people.

Annie and Armando Lualdi are cooking Minestrone in our kitchen in Chennai. They are here to make a documentary on India with my father. They know no English and we know no Italian, but my mother manages to communicate. My mother is gesturing animatedly, alternately laughing and hugging and speaking English with an Italian accent. She is moving like a dancer. There is no barrier. They understand each other perfectly and we are drawn into a lifelong bond between the families.

Our friends were from all corners of the globe. There was a time when I didn’t make a distinction between Indians and others. They were all just very interesting people. For my mother, friendship was a lifelong commitment and a valuable gift. She would do anything for a friend and give away her treasured belongings if they admired it. She was generous to a fault.

She taught us not to value possessions over people and to treasure knowledge and experience over wealth. And so though we had so little, as children we felt we were very fortunate. She was also a feminist and believed in equal rights. She abhorred men who used tradition and honour and customs as a cover up for exploiting women. On this issue she was blunt in expressing what she felt and many male friends have personally experienced this.

My mother wrote ‘Sita’, a very daring play where she portrayed Ravanna as the superior man as he loved Sita more than his kingdom and his life, whereas Rama loved his Kingship and Kingdom more than his wife. Such divergent radical thinking was the norm at home and conformity to status quo was not commended.

I am 13 years old and locked into my school principles office as a punishment for watching Dr. Zivago with my parents. I have been there all day and am terrified. I am desperate to escape. The office only has a partition – no wall. I find a chair, put it on a desk, jump over and go straight home to tell my mother. I run all the way. It is raining and I am soaked. Cold and humiliated by the punishment I run into my mother’s arms. She hugs and comforts me, wraps me in a shawl and gives me a mug of hot chocolate. I sit on the veranda watching the rain and I feel safe once again. No one can hurt me now.

The next day my mother comes with me to school. The principal tries to give her a lecture about morals and values and corrupting young minds. My mother is incensed. She tells the nun that she has sent me to school only for an academic education and nothing else. She makes it clear to my principal that she has no business interfering with the job of parenting.

It was in this cocoon of safety that I grew up. It was this security that gave me the courage to explore the unknown – this anchor that enabled me to feel grounded even when out of my depth – the guts to do things that no one else had done before – to discover through experimentation and learn from experience secure in the knowledge that I was loved. This was her gift.

On May 1st 1976 my mother wrote in her prison diary; “In a real dark night of the soul, it is always 3 o’clock in the morning day after day.” I wake up in a cold sweat. It is 3 o’clock in the morning. I keep my eyes closed to stay with my dream. The sound of the closing jail doors, the disappearing police van, her hand frozen in a wave. But I do not let it end there. I take her with me. Now we are sitting by the beach watching a glorious sunset, arms around each other. She is relaxed and at peace. I am safe. I have repaid my debt.

But now we are faced with a repeat performance – a dark shadow that is lengthening and threatening to engulf us and our Constitutional freedoms and fundamental rights. This time it is more subtle and savvy, but blatantly authoritarian all the same. My pact with my parents will not allow me to stand by a watch. I will fight it with all I have.